Two different versions of the crucifixion. One filled with symbols and statements, people and references. One with only two unspecified figures in addition to Christ in the middle. As we approach Good Friday, we remember the individual episodes of the day, the characters - major and minor - that appear and disappear through the story. But we remember that this story, which touches all of humanity, is also the story of one individual's suffering. Which aspect of the story - which version of the crucifixion - speaks most to you this year?

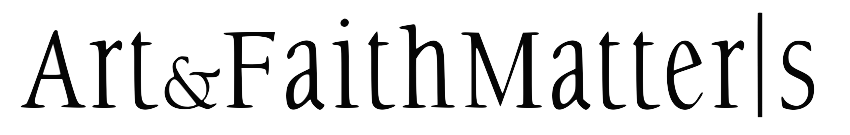

Philip Evergood. The New Lazarus. 1927-1954. NY: Whitney Museum of Art.

Evergood's large-scale work (58 1/4 × 93 3/8 × 2 5/8in) ties the story of Lazarus' resurrection to the story of Jesus' crucifixion. In the background, figures of ignorance cover their eyes and mouth and ears. The crucified Christ is off-center, placed left of center on the canvas. At the left a black figure hangs by hands tied to a tree near the bloody Lamb of God. At the right, soldiers stand while their fallen colleague is stretched out on the ground at the front of the canvas. Evergood wrote, "Christ, with all his generosity, his goodness, his love for people is crucified, drained of his blood, and left for the vultures to devour."

Augustus Vincent Tack. Mystical Crucifixion. Not dated. Washington, DC: Phillips Collection.

Tack's version of the crucifixion, by contrast, has only two figures, flanking the centered image of Christ on the cross. The composition is symmetrically balanced, with a sun/moon and a single figure seated on an outcropping of rocks on each side of the composition. The figure on the left (as we look at the painting) has his back turned to the viewer. Naked, with hands tied behind his back, he looks up at the figure of Christ. The figure on the right is clothed in what looks somewhat like the garb of a Roman soldier. Holding a sphere (the earth?) in the right hand and a sword in the left, the figure is not looking at Christ. The landscape is desolate. With no other supporting symbols or interpretation, we are left to find our own meaning in this version of the crucifixion, perhaps separate from the actual events of Good Friday.Which of the two speaks more to you in this season?